Abbie Trayler-Smith

still human still here

Still Human Still Here looks at the shocking, hidden lives of refused asylum seekers whose bids for sanctuary have been rejected by the British government.

I spent a year photographing men and women in the UK who have fled torture and persecution from troubled states including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Iran, Iraq, Somalia and Zimbabwe. They had hoped to find sanctuary in the UK but instead are enduring a new kind of torment – destitution.

All of the individuals featured in the work have been refused asylum and are living in extreme poverty rather than return to their home countries, in most cases out of fear of what might await them upon their return. With just a handful of possessions they move from place to place, sleeping in phone boxes, on night buses or park benches.

Two years ago Alain was the victim of a racist attack and blinded in one eye by a white man who stabbed him in the eye with a piece of broken glass. ‘As asylum seekers we have been punished twice – once back home and once here. IN Kinshasa I was tortured physically and here I’m tortured mentally. I’ve transferred from one prison to another.’

Following the rejection of her asylum claim Anne spent the next three years living in total destitution, much of the time sleeping outside. One night she was attached by a white gang while she was sleeping on park bench in Sunderland – two of the gang members raped her. She survived on an average of £3 a week, £5 on a good week. ‘About Africa they say ‘Make Porverty History’ because people there are living on a pound a day. But the government is doing the same thing to asylum seekers here by making them desititute.’

Following the rejection of her asylum claim Anne spent the next three years living in total destitution, much of the time sleeping outside. One night she was attached by a white gang while she was sleeping on park bench in Sunderland – two of the gang members raped her. She survived on an average of £3 a week, £5 on a good week. ‘About Africa they say ‘Make Porverty History’ because people there are living on a pound a day. But the government is doing the same thing to asylum seekers here by making them desititute.’

Anie spent her childhood in Congo where due to her political connections (her father was active in UNITA, an Angolan political party which at the time was committed to armed struggle but has since abandoned violence and has become part of the electoral process) she was imprisoned, tortured and raped.

She has difficulty walking because her legs are so badly scarred from her torture injuries and they still cause her a great deal of pain. She has been destitute since April 2008 and sometimes sleeps outside, sometimes sleeps on friends’ floors.

“My life here in England is full of pain and distress,” she said. “It’s hard for me to walk and I desperately need some accommodation. If I’m lucky friends give me £10 a week to live on but sometimes I have nothing.

On arrival in the UK Boni was shocked to find himself incarceratd again so soon after escaping from torture in Kinshasa. When he was release from detention he was destitute. He is now receiving section 4 support from the UK Border Agency but for fiteen months survived on almost nothing. ‘I don’t know what is happening to my case. I try to speak to my solicitor but for the last year he’s been too busy to take my calls.

Sleeping arrangements for destitute asylum seekers are many and varied but most of them are grim. Interviewees sleep on park benches, at railway stations, in the stairwells of council flats, in car park lifts, under bridges, in phone boxes, on night buses, in squats, abandoned cars or on friends’ floors or sofas. A few people sleep upright

on public toilets.

Sleeping outside makes asylum seekers particularly

vulnerable to a range of attacks and has led to a range of chronic health problems. Washing themselves and their clothes is often difficult for people sleeping outside.

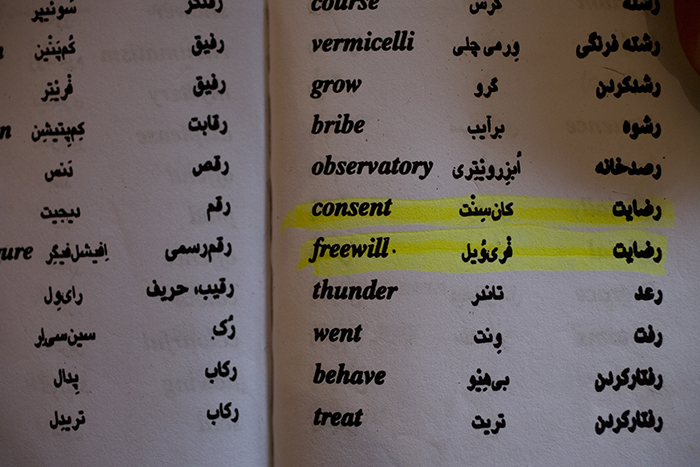

Hamid’s father ran a large and successful building and car business in Iran, the family was wealthy and after leaving school he worked for his father. He became involved in a political movement that opposed the government and as a result was detained and tortured. Hamid’s brother was executed by hanging by the Iranian government because he was politically active against the government.

Hamid managed to escape to the UK and after his asylum claim was refused he slept in abandoned cars, in the park, on buses and in phone boxes. He found food by going through the rubbish bins in restaurants.

“Sometimes I begged for £1 or £2 to buy food but begging made me feel very ashamed. I mainly survived by eating chips and pitta bread,” he says.

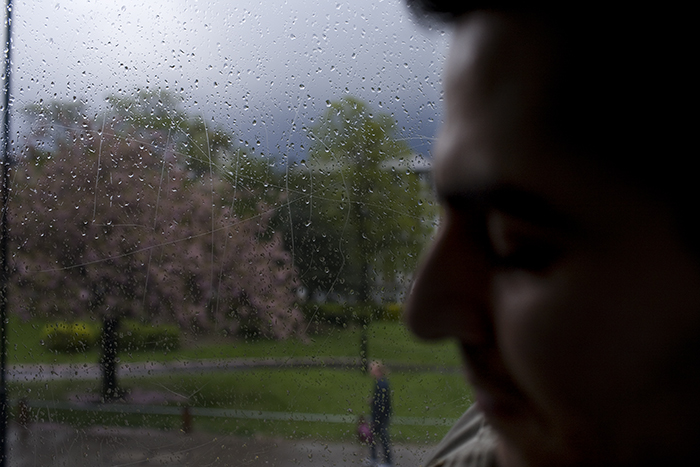

“When you’re sleeping outside one night feels like one year because it’s so cold. I never managed to sleep for more than an hour or two and when it’s raining it’s hard to sleep for more than fifteen minutes at a time.”

Hamid’s father ran a large and successful building and car business in Iran, the family was wealthy and after leaving school he worked for his father. He became involved in a political movement that opposed the government and as a result was detained and tortured. Hamid’s brother was executed by hanging by the Iranian government because he was politically active against the government.

Hamid managed to escape to the UK and after his asylum claim was refused he slept in abandoned cars, in the park, on buses and in phone boxes. He found food by going through the rubbish bins in restaurants.

“Sometimes I begged for £1 or £2 to buy food but begging made me feel very ashamed. I mainly survived by eating chips and pitta bread,” he says.

“When you’re sleeping outside one night feels like one year because it’s so cold. I never managed to sleep for more than an hour or two and when it’s raining it’s hard to sleep for more than fifteen minutes at a time.”

Hamid’s father ran a large and successful building and car business in Iran, the family was wealthy and after leaving school he worked for his father. He became involved in a political movement that opposed the government and as a result was detained and tortured. Hamid’s brother was executed by hanging by the Iranian government because he was politically active against the government.

Hamid managed to escape to the UK and after his asylum claim was refused he slept in abandoned cars, in the park, on buses and in phone boxes. He found food by going through the rubbish bins in restaurants.

“Sometimes I begged for £1 or £2 to buy food but begging made me feel very ashamed. I mainly survived by eating chips and pitta bread,” he says.

Monique had completed three years of a four-year course in electrical engineering at university in the capital of DRC, Kinshasa, when disaster struck. Until then she had led a comfortable life, her father was a doctor and her family placed a great deal of emphasis on education. She attended a student demonstration opposing president Kabila and to her horror witnessed some of her friends shot by government forces who wanted to put an end to the demonstration.

Monique was arrested, detained and tortured. Friends helped get her released and whisked out of the country.

She arrived in December 2002, claimed asylum and had her case rejected. In December 2007 her support was cut off and she became destitute. Some nights she has slept in a church in Tottenham, at other times with friends or in the park.

“I hate to sleep in the park because it’s very dangerous,” she says. Nightmares about being forcibly returned to Congo plague her.

“If they send me back they might as well put me in a coffin-shaped suitcase.”

She survives on around £5 per week given to her by friends and sometimes goes two days without any food at all.

Her asylum claim was refused in 2003, for 5 years she has survived on the kindness of friends and charities for food handouts. She has no idea what the future holds. She is currently on Section 4 support (£35 supermarket vouchers and no choice accommodation) by UKBA.

“I have no family, no papers, no work. I take tablets for depression because I can’t sleep at night. We have the status of animals here. All we are allowed to do is eat, drink and sleep, that’s the same as animals do. The situation in Eritrea is too dangerous for me to return now. Lots of people are being killed there. I pray to God to change my life and take my problems away so that I will once more be able to look after my children.”

Shorsh was a student in Iraq and had suffered many problems under Saddam Husein’s rule because he is Kurdish. He was falsely blamed for planting a bomb in his neighbourhood and was then approached by some of Saddam’s men who tried to force him to join the Ba’ath Party. He was not involved in politics of any description and he knew he had to escape before he was accused of something else he hadn’t done, arrested and detained

He is now entering his third year of destitution and is supported entirely by friends who have accommodation and allow him to sleep on their floors and sofas.

“People here don’t understand how much we long to go home and why we can’t return,” he says.